How do we ensure our IoT products process information lawfully?

-

Due to the Data (Use and Access) Act coming into law on 19 June 2025, this guidance is under review and may be subject to change. The Plans for new and updated guidance page will tell you about which guidance will be updated and when this will happen.

How do we choose the right lawful basis?

To process personal information, you must have a valid lawful basis. There are six available lawful bases for processing:

- consent;

- contract;

- legal obligation;

- vital interests;

- public task; and

- legitimate interests.

No single basis is ‘better’ or more important than the others. The most appropriate basis for your processing will depend on your purpose and relationship with the person.

With most IoT products and associated services, the most relevant lawful bases are consent, contract, legal obligation and legitimate interests. If you use storage and access technologies, you must use consent unless a PECR exemption applies.

Most lawful bases require that processing is ‘necessary’ for your specific purpose(s). You must determine your lawful basis before you begin processing. You should document it – and remember, you must tell people what lawful basis you are using in the privacy information you give them.

Read our guidance on storage and access technologies for more information about the interplay between PECR rules and choosing your lawful basis.

Special category conditions

You must have a valid condition for processing special category information.

Article 9 of the UK GDPR contains 10 conditions for processing special category information. Schedule 1 of the DPA 2018 provides further requirements for meeting some of these conditions. Read our guidance on special category information for more details about the conditions.

Further reading – ICO guidance

How do we ask for consent in IoT products?

You must ensure that consent is:

- freely given;

- specific;

- informed;

- unambiguous; and

- given by a clear affirmative act.

You must ensure that it represents a person’s active choice and be as easy to withdraw as it is to give.

If you make consent a precondition of the service but the processing is not necessary for that service, the consents you obtain are invalid.

How do we inform people?

Being informed means people know what information you want to process and why, and also the consequences of giving their consent.

IoT products can have different interfaces, including a small or large screen, voice and sound interface, mobile app or web app. You should consider what is the best method for your relevant interface when you ask for consent and when you give people the information they need to make decisions.

For IoT products with no screens or small screens, you should make your requests for consent available somewhere else (eg on an accompanying mobile app). This is because a product without a screen doesn’t provide a way to show a consent request. And it may be difficult for you to provide the required information on a small screen.

Example

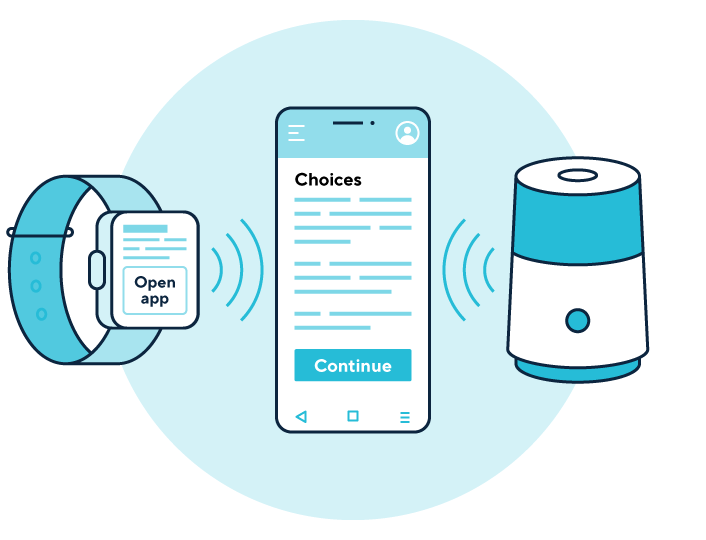

A graphic shows:

- a smart watch (ie a product with a small screen); and

- a smart speaker (ie a product with no screen)

handing over to the product’s accompanying mobile app to allow users to make choices about the processing of their personal information.

How you present choices in an interface can help people make better decisions, but it can also affect their actions and, if done badly, invalidate their consent.

If your IoT product is aimed at children or likely to be used by them, the UK GDPR and DPA 2018 specify that if you rely on consent for any aspects of your processing, you must get parental authorisation for children under 13. You should refer to the Children’s code for more detail on how to approach your requests for consent from a child.

What does ‘freely given’ mean?

You must give people genuine choice and control over how you use their personal information. If people don’t have a real choice, their consent is not freely given and is invalid.

People must be able to refuse consent without detriment as well as to withdraw it easily at any time.

You must ensure that the consent you obtain is unambiguous. So your consent interfaces must involve a clear affirmative action (an opt-in). Pre-ticked opt-in boxes are specifically non-compliant under UK GDPR.

If you offer multiple choices in a consent interface, you must not make one more appealing or prominent than another. This is likely to invalidate the user’s consent.

You must not ask for consent in quick succession or repeatedly.

You could introduce positive friction into the consent mechanisms to help people consider their choices. Positive friction might require a user to slow down as they interact with consent mechanisms and consider their choices.

You may want to avoid disrupting the user’s experience, but this does not override your need to ensure that consent requests are valid – so some level of disruption may be necessary. However, you should be careful to avoid making consent requests unnecessarily disruptive.

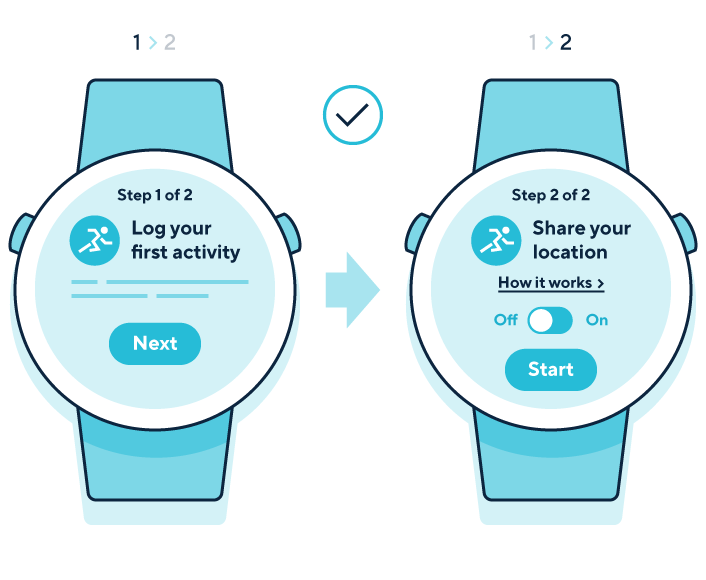

Example

A graphic shows a smartwatch being set up by a user. The user has gone through 12 of the 20 steps of the set-up where they have been asked to make choices about the processing of their personal information. This set-up shows requests for consent in quick succession. The user is unlikely to be able to consider all the requests to provide freely given consent.

Example

A graphic shows a smartwatch being set up by a user. The user has gone through 12 of the 20 steps of the set-up where they have been asked to make choices about the processing of their personal information. This set-up shows requests for consent in quick succession. The user is unlikely to be able to consider all the requests to provide freely given consent.

Similarly, you must not use option labels that invite guilt or another negative emotion. Sometimes known as ‘confirmshaming’, this can bias people’s choices and invalidate their consent.

You must not use ‘biased framing’ to emphasise the supposed benefits of one particular option to make it more appealing or the supposed risks of another to discourage people from selecting it.

You must give people the option to refuse and withdraw consent without being penalised.

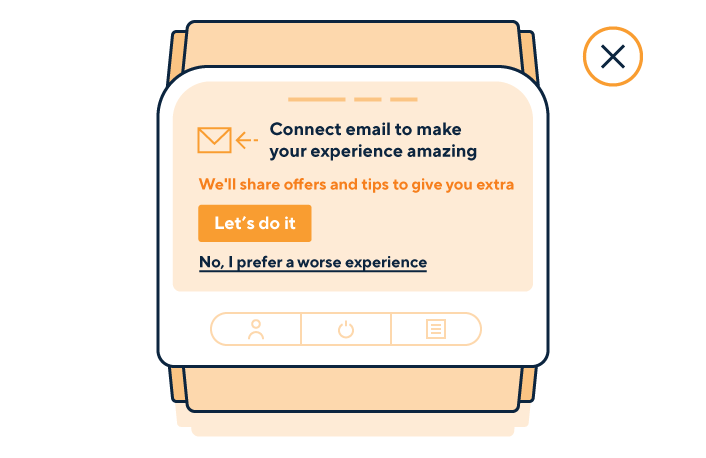

Example

A graphic shows a smart blood pressure monitor with a digital screen on the product displaying a request to connect user’s email using nudging techniques. The blood pressure monitor uses ‘confirmshaming’ by saying ‘Connect email to make your experience amazing’ and the option to opt out is labelled as “No, I prefer a worse experience’. The options to opt in and out are displayed using biased framing, making the opt-in option more visible and brighter. The option to opt out is less prominent.

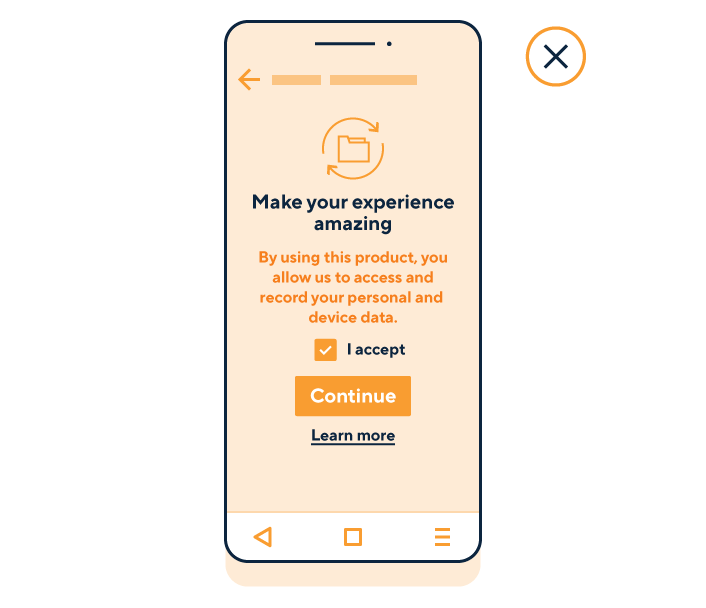

Example

A graphic shows a mobile app making a consent request for the processing of personal information. The consent request uses biased framing, where the option to opt in is more prominent, using brighter colours, and a pre-ticked box saying ‘I accept’. The user is presented with a button to continue. It is not clear from the design that they could opt out. There is a link to ‘learn more’ about the processing of information.

What do you mean by ‘specific and informed’?

For consent to be specific and informed, you must tell people about:

- who you are;

- why you want their personal information;

- what you’re going to do with it;

- who you’ll share it with; and

- how they can withdraw their consent at any time.

These requirements are separate from your obligations to provide privacy information under the right to be informed.

You must give granular options to consent separately to different purposes.

You must separate consent from terms and conditions. The rules about consent requests are separate from your transparency obligations under the right to be informed, which apply whether or not you are relying on consent.

You should think carefully about when to use consent interfaces. Use too few and you may not comply with UK GDPR requirements. However, overusing unnecessary consent pop-ups will cause decision fatigue, training people to accept information sharing or other uses of their information blindly in every product they encounter.

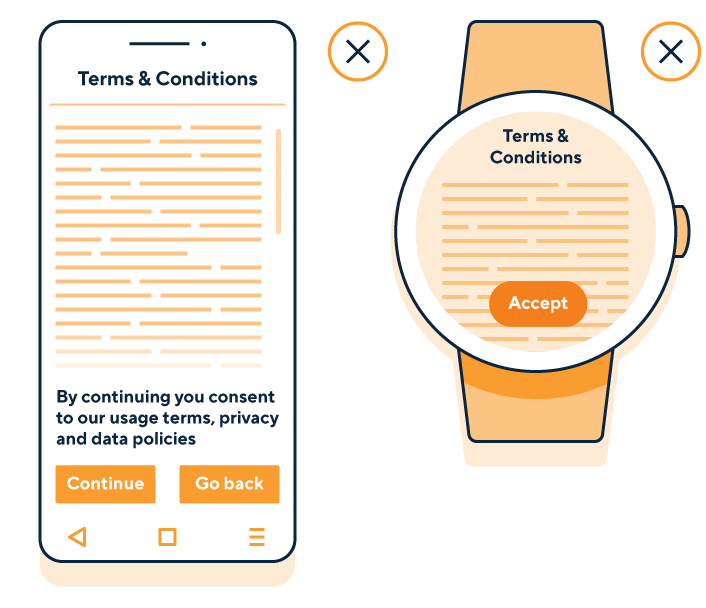

Example

A graphic shows an outline of a mobile app displaying the bundling of terms and conditions, privacy policy and consent. The graphic includes an indication of a block of text that the user needs to scroll through. The block of indicated text is overlayed with a message saying, ‘By continuing you consent to our usage terms, privacy and data policies’. The user is presented with two buttons, one for ‘continue’ and the other to ‘go back’.

Another graphic shows a smartwatch displaying the bundling of terms and conditions and privacy terms on a small screen. There is a single button to ‘accept’ the conditions without the possibility to decline them.

You must tell the person the controller’s identity. This means you need to identify yourself, and also name any third-party controllers who will be relying on the consent.

You must offer people a way to reopen consent interfaces later on. It must be as easy to withdraw consent as it is to give it.

You could provide ‘privacy settings’ in the product settings where your users could access consent interfaces for different types of processing.

What do you mean by unambiguous indication?

You must ensure that it is obvious that the person has consented, and what they have consented to.

The key point is that you must make all consent opt-in consent (ie a positive action or indication – there is no such thing as ‘opt-out consent’). Failure to opt out is not consent as it does not involve a clear affirmative act.

Relying on silence, inactivity, default settings, pre-ticked boxes or your general terms and conditions does not lead to valid consent. Neither does taking advantage of inertia, inattention or default bias in any other way.

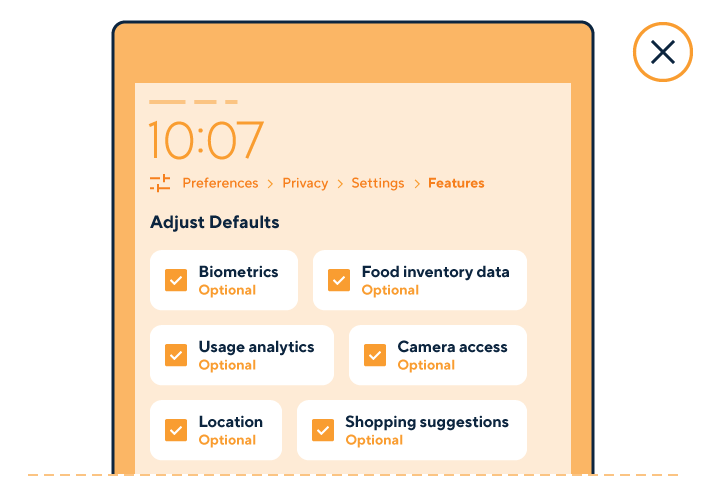

Example

A graphic of a screen on a smart fridge shows ‘preferences’ settings. The privacy settings are hidden on the fourth layer of the settings and aren’t named intuitively for users to find them easily. The graphic shows types of personal information the fridge is processing, including biometrics, location, food inventory data, camera access, usage analytics and shopping suggestions. Each data type has been marked as ‘optional’. The categories of personal information have been pre-ticked by default to indicate that all this information will be processed.

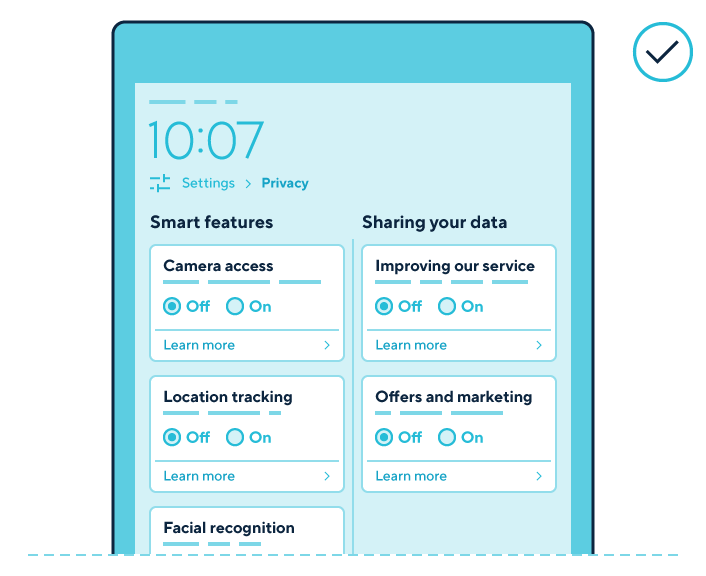

Example

A graphic of a screen on a smart fridge shows settings for privacy on the second layer of the settings. Privacy settings are logically divided into ‘smart features’ controls, including camera access, location tracking and facial recognition, and controls for ‘sharing your data’, including controls for ‘improving our service’ and ‘offers and marketing’. Each control is set to ‘off’ by default and there is an option to click on ‘learn more’ for information about what each setting does with personal information.

What is ‘explicit consent’?

The UK GDPR does not define explicit consent. In practice, it is not very different from the usual high standard of consent. This is because all consent must involve a specific, informed, freely given and unambiguous indication of the person’s wishes.

The key difference is that ‘explicit’ consent requires a clear statement (whether oral or written).

You must ask users of IoT products for their explicit consent if you are processing their special category data and explicit consent is your chosen condition for processing.

Refer to our guidance on consent for more information about how to phrase explicit consent requests.

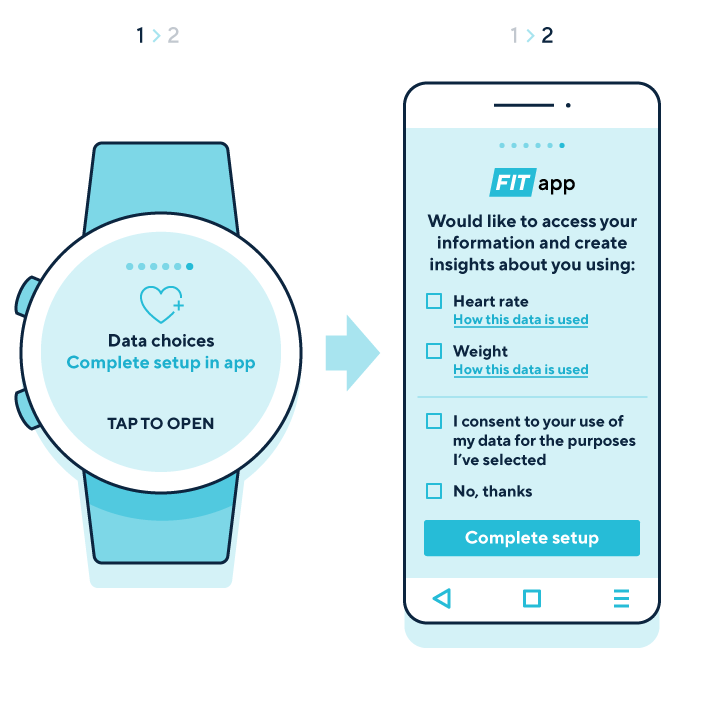

Example

A graphic of a smartwatch shows a screen prompting users to finish setting up their data-processing choices in the mobile app. A graphic of a mobile app next to the smartwatch shows a screen where users are asked to provide explicit consent to processing special category health data, including heart rate, for the smartwatch’s fitness-tracking function.

When should we ask for consent?

If you are relying on consent as your lawful basis for processing people’s information, you must ask for consent when you start your processing. You may choose not to start all your processing at the same time.

If you start processing different types of personal information at different times, you should consider finding the right moments to ask people for consent.

In practice this means you should think about asking for consent at appropriate points in the user journey.

While the set-up of a product is a logical point in the user journey, it is not necessarily the only time to ask for consent. There may be other moments when it will be appropriate to do so. This also means you aren’t overloading your users with consent requests all at once and you can make them more specific.

Some of the moments you should consider include:

- during product set-up;

- when the IoT product collects personal information about a new person or when a new account is added;

- when a user enables a new product feature after initial set-up, and the feature requires consent for additional types of information for a new purpose (eg location data, health information);

- if a product update changes how personal information is processed; and

- if a young person becomes old enough to give consent for themselves.

What methods can we use to obtain consent?

Whatever method you use, consent must be an unambiguous indication by clear affirmative action. This means you must ask people to actively opt in. Examples of active opt-in mechanisms include:

- ticking an opt-in box;

- clicking an opt-in button or link online;

- selecting from equally prominent yes or no options;

- choosing technical settings or preference dashboard settings;

- responding to an email requesting consent;

- answering yes to a clear oral consent request; and

- responding to just-in-time notices.

Example

A graphic of a smart speaker shows the speaker using an oral consent request to allow the user to make choices about whether their personal information is processed, offering yes or no answers to the question ‘Can I process your voice data to create a more personalised experience?’

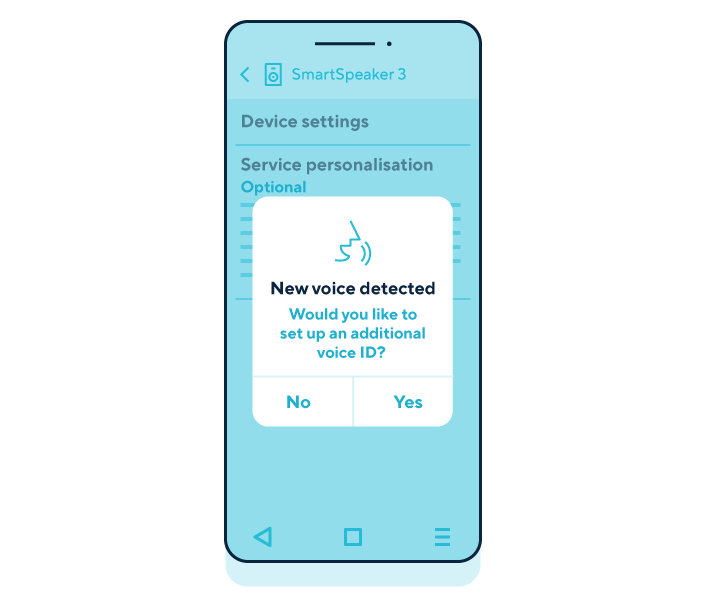

Example

A graphic shows an accompanying mobile app displaying a just-in-time notice saying that a smart speaker has detected a new voice. The app is asking ‘Would you like to set up an additional voice ID?’, offering yes and no answers of equal prominence.

Further reading – ICO guidance

How do we ensure people can withdraw consent?

Your users must be able to withdraw consent at any time. This means you must design your consent mechanism with technical capability for users to withdraw consent as easily as they gave it.

You must also tell people how they can withdraw consent in your consent mechanism.

You should make any effects of withdrawing consent clear – for example, if people can no longer use certain features of your IoT product if they withdraw consent.

How do we ask for consent from multiple users?

If your IoT product can be used by multiple users, you must consider ways to gather consent for processing personal information from them if you’ve chosen it as your lawful basis.

Gathering consent from multiple users where not everyone has an account for your IoT product may be difficult. You should consider giving people the option to create multiple accounts for the same product if this is likely to improve their ability to exercise more control over their personal information.

You should consider in which instances you may be able to ask different users for their consent to processing in a meaningful way. This may depend on how you design the hierarchy of multiple users in your product.

If your hierarchy set-up for multiple users relies on a main account holder and an additional account holder – where you expect the main account holder to make most decisions about processing by the IoT product – you should make sure you clearly explain to the additional account holder what each account holder can control.

If your set-up for multiple users is designed with a more equal approach to account holders, you should make sure you clearly explain what each account holder can control about processing by the IoT product. You should include notifications for all users when you change how their personal information is processed.

When is consent not appropriate?

If for any reason you cannot offer people a genuine choice over how your IoT product processes their personal information, consent is not the appropriate basis for your processing – for example, if you would still process their personal information on a different lawful basis if they refused or withdrew consent.

Consent is also unlikely to be the appropriate lawful basis if you ask for it as a precondition of using your IoT product and its associated app.

Example

A parent buys a children’s GPS tracker for their eight-year-old child. The location is core to the service of the tracker, meaning the children’s tracker wouldn’t be able to function without it.

Asking for consent to process the information about the child’s location is not the most appropriate lawful basis because providing this information is a condition of the service. It is more appropriate to use performance of a contract as a lawful basis to process GPS data.