Pseudonymisation

-

Due to the Data (Use and Access) Act coming into law on 19 June 2025, this guidance is under review and may be subject to change. The Plans for new and updated guidance page will tell you about which guidance will be updated and when this will happen.

At a glance

- Pseudonymisation refers to techniques that replace, remove or transform information that identifies people, and keep that information separate

- Pseudonymised personal data is in scope of data protection law.

- Pseudonymisation has many benefits. It can help you to reduce the risks your processing poses:

- implement data protection by design;

- ensure appropriate security; and

- make better use of personal data (eg for research purposes and general analysis).

- Take care not to confuse pseudonymisation with anonymisation. Pseudonymisation is a way of reducing risk and improving security. It is not a way of transforming personal data to the extent the law no longer applies.

- The DPA 2018 contains two criminal offences that address the potential harms that result from unauthorised removal of pseudonymisation.

- There are many pseudonymisation techniques. Some will help you achieve pseudonymisation as defined by the law. Others may not, but can still be useful technical measures from a security perspective.

In detail

- What is pseudonymisation?

- Is pseudonymised data still personal data?

- What are the benefits of pseudonymisation?

- How can pseudonymisation help us to reduce risk?

- Can pseudonymisation help us process data for other purposes?

- Are there any offences relating to pseudonymisation?

- How should we approach pseudonymisation?

- What pseudonymisation techniques should we use?

- How should we assess the risk of attackers reversing pseudonymisation?

- What organisational measures should we consider for pseudonymisation?

What is pseudonymisation?

Pseudonymisation has a specific meaning in data protection law. This may differ from how it is used in other circumstances, industries or sectors.

Article 4(5) of the UK GDPR defines pseudonymisation as:

“…processing of personal data in such a manner that the personal data can no longer be attributed to a specific data subject without the use of additional information, provided that such additional information is kept separately and is subject to technical and organisational measures to ensure that the personal data are not attributed to an identified or identifiable natural person.”

There is no equivalent definition in the law enforcement or intelligence services regimes in the DPA 2018, but similar considerations apply.

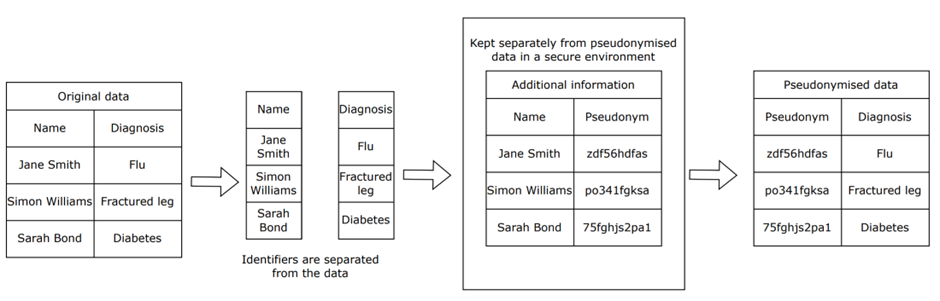

Pseudonymisation starts with a single input (the original personal data) and ends with two outputs (the pseudonymised dataset and the additional information). Together, these two outputs can reconstruct the original personal data. However, for the people concerned, each output only has meaning when combined with the other.

Example

The diagram below shows a simple example of pseudonymisation, where the identifiers are removed and replaced with a pseudonym, which is stored separately.

Pseudonymisation therefore refers to techniques that replace, remove or transform information that identifies a person and store it separately. For example, replacing one or more identifiers which are easily attributed to people (such as names) with a pseudonym (such as a reference number).

If the data is pseudonymised, you can tie that pseudonym back to the person if you have access to the additional information. However, you must:

- hold this information separately; and

- keep it secure.

Data protection law specifically mentions “unauthorised reversal of pseudonymisation” as something that can result in harm. You must assess the likelihood and severity of this risk and mitigate it appropriately.

Further reading – ICO guidance

Is pseudonymised data still personal data?

Yes. Pseudonymised data is personal data in the hands of someone who holds the additional information.

However, it does not change the status of the data as personal data when you process it in this way.

This is because data protection law is clear that information is personal data if a person is identified or identifiable, directly or indirectly.

The core definition of pseudonymisation describes it as processing of personal data in a particular manner. Additionally, Recital 26 of the UK GDPR says that:

If you share pseudonymised data (but not the additional information) with another organisation, it may be anonymous information in their hands.

Further reading – ICO guidance

The section Do we need to consider who else may be able to identify people from the data? provides further information on assessing the identifiability of pseudonymised data without additional information with another organisation.

What are the benefits of pseudonymisation?

Pseudonymisation can reduce the risks to people. It can also help you meet your data protection obligations, including data protection by design and security.

When you apply pseudonymisation properly, it can help to:

- reduce the risk your processing poses to people’s rights;

- enhance the security of the personal data you process;

- support re-use of personal data for new purposes;

- support your overall compliance with the data protection principles;

- provide suitable safeguards to mitigate the risk of an international transfer of personal data;

- build people’s trust and confidence in how you process their data; and

- demonstrate you have put appropriate safeguards in place, as you are required to do when using personal data for research purposes.

Pseudonymisation can enable greater utility of data than anonymisation. However, you should still consider whether you can meet your objectives by using anonymous information.

How can pseudonymisation help us to reduce risk?

Recital 28 of the UK GDPR says that:

Data protection law doesn’t include a specific definition of risk. But it does make it clear that this is about the risks to people’s rights and freedoms. For example, Recital 75 links these risks to the potential for harm or damage:

So, pseudonymisation is relevant for your assessment of these risks. For example, in data protection impact assessments (DPIAs) or legitimate interests assessments (LIAs), you could detail specific pseudonymisation techniques you use and show how they mitigate the particular risks your processing poses.

Pseudonymisation is also relevant as a risk reduction measure in other areas, such as:

- data protection by design and security; and

- personal data breaches.

Security and data protection by design

You must put in place appropriate technical and organisational measures to:

- implement the data protection principles effectively and integrate necessary safeguards into the processing. This is “data protection by design”; and

- ensure a level of security appropriate to the risk the processing poses. This is “the security principle”.

The law specifically references pseudonymisation in both of these requirements.

If you apply pseudonymisation properly, it can be a useful mechanism to enhance the security of personal data and support your overall compliance with the data protection principles.

Pseudonymisation is particularly relevant in the context of the data minimisation principle.

This is because it can limit the level of identifiability in the data to what is necessary for the purpose.

When you consider pseudonymisation techniques, you must take into account the:

- state of the art and costs of implementation of any measures;

- nature, scope, context and purpose(s) of your processing; and

- risks your processing poses to people’s rights and freedoms.

When you assess the state of the art, you should consider whether the technique is suitably robust, for example, is it:

- resistant to known attacks;

- scalable; and

- not cost-prohibitive to implement?

The nature, scope and purposes of the processing influence the type of pseudonymisation technique that is appropriate. You should consider whether your chosen approach allows you to fulfil your purposes and also whether the measures you choose can reduce the risks to people to an acceptable level.

Not all pseudonymisation techniques are equally effective, and they may not have the same implementation costs or requirements. You should choose your pseudonymisation technique by finding the optimal approach to achieving data protection by design and security.

Personal data breaches

Pseudonymisation techniques can reduce the risk of harm to people that may arise from personal data breaches. This can also form part of your assessment of the likelihood and severity of any impact of a personal data breach.

Pseudonymisation may be relevant when you assess whether you should notify people of the personal data breach. Under Article 34 of the UK GDPR, you must notify people about a data breach without undue delay, if the data breach results in a high risk to their rights and freedoms, unless you have:

“…implemented appropriate technical and organisational protection measures, and those measures were applied to the personal data affected by the data protection breach, in particular those that render the personal data unintelligible to any person who is not authorised to access it, such as encryption.”

Although this does not specify pseudonymisation, it broadly describes technical and organisational measures. These technical measures can include pseudonymisation. It can provide another line of defence in the security context, reducing the level of risk for those affected.

If a personal data breach takes place, you must assess whether the pseudonymisation measures you have in place prevent the breach causing a high risk for the people concerned. You still must inform the ICO in the event of a data breach. Depending on the circumstances of the breach (eg there is still risks to people), we may direct you to notify the affected people.

Can pseudonymisation help us process data for other purposes?

Data protection law may allow you to repurpose personal data for some types of processing, if appropriate safeguards such as pseudonymisation are in

place. For example, for research, further analysis or compatible purposes. This means that pseudonymisation can be a useful tool to enable further processing of personal data beyond its original purpose.

This does not mean pseudonymisation automatically allows you to undertake this further processing in all cases. However, it can be an important way for

you to demonstrate how you protect personal data, if you do so. It is therefore a factor whenever you are considering whether you can process personal data for other purposes.

If your purposes change over time or you want to use data for a new purpose which you did not originally anticipate, you must only go ahead if:

- the new purpose is compatible with the original purpose;

- you get a person’s specific consent for the new purpose; or

- you can point to a clear legal provision requiring or allowing the new processing in the public interest.

Pseudonymisation is relevant when you are considering compatibility instead of consent or legal provisions. For example, if you:

- undertake further processing for archiving, scientific or historical research, and statistical purposes, which are automatically considered to be compatible purposes; or

- want to undertake further processing for other purposes, and need to assess whether these are compatible with your initial purpose.

Pseudonymisation also allows you to perform general analysis. You could do this activity as part of the further processing.

Other compatible purposes

Article 6(4) of the UK GDPR says that when deciding if a new purpose is compatible with your original purpose, you must take into account:

- any link between your original purpose and the new purpose;

- the context in which you originally collected the personal data. In particular, your relationship with the person and what they would reasonably expect;

- the nature of the personal data (eg whether it is special category data or data relating to criminal convictions or offences);

- the possible consequences for people of the new processing; and

- whether there are appropriate safeguards (eg encryption or pseudonymisation).

Pseudonymisation does not necessarily mean that you can decide your new purpose is compatible in all cases. It is one of several factors you must consider in this assessment. If your new purpose is compatible, you don’t need a new lawful basis for the further processing.

However, you need to remember that if you originally collected the data on the basis of consent, you should get fresh consent to ensure your new processing is fair and lawful or you can rely on another basis such as legitimate interests or public task depending on your circumstances. You also must update your privacy information so that your processing is still transparent.

General analysis

Recital 29 of the UK GDPR says that:

“In order to create incentives to apply pseudonymisation when processing personal data, measures of pseudonymisation should, whilst allowing general analysis, be possible within the same controller when that controller has taken technical and organisational measures necessary to ensure, for the processing concerned, that this Regulation is implemented, and that additional information for attributing the personal data to a specific data subject is kept separately. The controller processing the personal data should indicate the authorised persons within the same controller.”

This means you could perform this general analysis on pseudonymised data within your organisation, however you must:

- implement the technical and organisational measures necessary to ensure data protection compliance; and

- ensure that you keep additional information for attributing the data to a specific person separately.

Data protection law does not define general analysis. However, if you intend to analyse data relating to specific people (eg their behaviour, location, characteristics) for the purposes of taking actions about them, this analysis is not general in nature.

In practice, general analysis may be something you undertake for the two purposes detailed above. It can bring many benefits, depending on the purposes you do it for. For example, pseudonymising data about how people use your products and services, and then deriving insights and trends from that data. This may allow you to develop new, innovative services or improve existing ones.

This is particularly the case if anonymous information is less useful. However, you should carefully consider whether you can achieve these objectives using such information first.

When you perform general analysis, you should indicate the authorised people within your organisation that have access to the additional information. You should also update this, if you make any personnel changes in the future.

Further reading – ICO guidance

Are there any offences relating to pseudonymisation?

Yes. Section 171 of the DPA 2018 contains two criminal offences relating to re-identification. We call these the ‘re-identification offences’. They cover the identification of people from pseudonymised data and ineffectively anonymised data.

The first, at section 171(1), is about the act of re-identification. It states that:

“It is an offence for a person knowingly or recklessly to re-identify information that is de-identified personal data without the consent of the controller responsible for de-identifying the personal data.”

The second, at section 171(5), is about processing the personal data after the act of re-identification takes place. It states that:

“It is an offence for a person knowingly or recklessly to process personal data that is information that has been re-identified where the person does so –

- without the consent of the controller responsible for de-identifying the personal data, and

- in circumstances in which the re-identification was an offence under subsection (1).”

The definition of ‘de-identified’ data is:

“…personal data […] processed in such a manner that it can no longer be attributed, without more, to a specific data subject” (emphasis added).

This is not directly equivalent to the definition of pseudonymisation as there is no requirement for the additional identifying information to be retained and held separately and securely.

In other words, it may include any information where the ‘direct’ identifiers have been stripped out. But the people the information relates to are indirectly identifiable using additional information or other techniques. This is the case, even if there’s no specific ‘key’ held to enable deliberate identification. For example, the use of decryption technologies or hacking techniques aimed at breaking the de-identification process.

This may be due to several factors, such as ineffective application of anonymisation techniques, advances in re-identification techniques or previously unknown re-identification attacks.

In summary, reversing pseudonymisation or ineffective anonymisation by attempting to attribute the data to a specific person is a crime. You must not try to match up pseudonymous personal data to the person it relates to, or attempt to re-identify people in information believed to have been anonymised, unless the controller who pseudonymised or anonymised the data agrees to you doing so.

Are there any defences?

Yes. For example, re-identification is allowed if you can prove that it was:

- necessary for the purposes of preventing or detecting crime;

- required or authorised by law or by a court order; or

- in the circumstances, justified as being in the public interest.

The defences also include where the person charged can prove that they acted:

- in the reasonable belief that they are the person the information relates to, have the consent of that person, or would have had such consent if the person had known about the reidentification and its circumstances;

- in the reasonable belief that they are the organisation responsible for the de-identification, have the consent of that organisation, or would have had such consent if the organisation had known about the re-identification and its circumstances; and

- for the “special purposes”, with a view to publication of any journalistic, academic, artistic or literary material, and in the reasonable belief that the re-identification was justified as being in the public interest in the circumstances.

Re-identification as a security testing measure

The law allows for re-identification if this is to test the effectiveness of an anonymisation or pseudonymisation technique. For example:

- testing the effectiveness of your own security measures; or

- security or technology researchers who test those of others.

This is not an offence provided you meet the following two conditions:

- condition one: The person is testing the effectiveness of the de-identification systems an organisation uses, where they reasonably believe the testing is justified as being in the public interest and where they do not intend to cause or threaten damage or distress; and

- condition two: The person notifies either the ICO or the organisation responsible for the de-identification about the re-identification.

If you test the measures of other organisations and successfully re-identify people, you must:

- let those organisations know as soon as possible; and

- where feasible, let them know within 72 hours of becoming aware of it.

If there are multiple organisations responsible for the initial de-identification, you can meet condition two’s requirements by notifying one or more of them.

You can only rely on the effectiveness testing provision if you are acting in the public interest. The defence does not legitimise unlawful or harmful practices. You are likely to be committing a criminal offence, if you reverse pseudonymisation, or information thought to be anonymised, and cause or threaten harm to people or organisations.

Although the explanatory notes are not part of the law, they explain what each provision of the DPA 2018 means in practice and provide background information on the intended outcomes of the provisions.

Further reading – ICO guidance

Exemptions – the “special purposes”

The DPA 2018’s explanatory notes provide further information on how the re-identification offences apply to pseudonymised data (external link)

How should we approach pseudonymisation?

You are responsible for deciding whether to implement pseudonymisation and how to do so. You should clearly establish what you want to achieve and the most appropriate technique. An inadequate level of pseudonymisation does not meet the legal definition of pseudonymisation in data protection law, even if the technique you use may fit under existing technical meanings of the term.

You should:

- define the goals: what does your use of pseudonymisation intend to achieve?;

- detail the risks: what types of attack are possible, who may attempt them, and what measures do you need to implement as a result?;

- decide on the technique: which technique (or set of techniques) is most appropriate?;

- decide who does the pseudonymisation: you or a processor?; and

- document your decisions and risk assessments (eg in your DPIA, LIA or record of processing activities).

While this is not an exhaustive list of relevant considerations, you should address them together due to how they relate to each other.

Define your goals

Overarching goals of pseudonymisation can include:

- ensuring that parties other than yourself (and, where appropriate, any processor you may use) cannot identify people;

- ensuring that third parties cannot access or reconstruct the additional information;

- enabling data accuracy (eg by assigning a particular pseudonym to a person that allows you to verify their identity); and

- achieving data minimisation (eg if the purposes of your processing do not require you to identify people).

You should ensure that once you implement pseudonymisation, you mitigate any risk of unauthorised reversal of it. To do this, you should consider any potential source of risk (eg a malicious attacker or an insider threat).

You should also consider whether the pseudonymisation technique you use is useable and scalable, so that it is practical for the processing activity you want to carry out.

Detail the risks

When assessing what pseudonymisation techniques to use and how to implement them, you should take into account the type of attacker that may exist. For example, it is good practice to consider:

- insider threats – someone with specific knowledge, capabilities or permissions, either in your organisation, a processor you use, or another entity you engage (eg a trusted third party);

- external threats – someone who may not have direct access to the additional information, but wants to increase their knowledge about the pseudonymised dataset (eg by re-identifying the people within the dataset); and

- the likely goals of any attack – an attacker may want to achieve different goals (eg identification attacks, where the attacker seeks to re-identify people (either a subset, or all of them).

Further reading – ICO guidance

We discuss the methodology to assess the risk of singling out a person in the section How do we ensure anonymisation is effective?.

Decide on the technique

When deciding on a pseudonymisation technique, you should take into account:

- the nature, scope, context and purpose of the processing;

- the risk factors you identify; and

- the privacy protection, utility and scalability goals your processing requires.

You should explore the availability of existing solutions to meet your goals, together with their strengths and limitations, in your decision-making process. You should choose the appropriate technique after considering:

- the risk of identification for the part of the data that you will transform by the pseudonymisation technique;

- the security measures (both technical and organisational) you can put in place to protect the additional information that would allow the pseudonymised data to be re-identified; and

- the required utility and accuracy of the data for the purposes of the processing.

You should also have appropriate processes in place for regularly testing, assessing and evaluating the effectiveness of the pseudonymisation techniques you use.

Decide who performs the pseudonymisation

Different parties may be involved in any pseudonymisation process. There is no one-size-fits-all approach. It is ultimately a decision for you to take based on your specific circumstances.

Pseudonymisation may be performed by:

- you;

- a processor working on your behalf (eg if they have specialist expertise and resources to help you achieve your goals); or

- another party working with you as a joint controller.

You should identify roles and responsibilities of any party involved in the pseudonymisation process.

You could also consider separating the functions. For example, clearly specifying and distinguishing between the people that:

- carry out the pseudonymisation processes;

- are authorised to access the additional information; and

- undertake any subsequent processing of the pseudonymised data (eg if you are performing general analysis for certain purposes).

Further reading – ICO guidance

Document the outcome

It is important that you clearly document your decision-making processes and detail the steps you take.

This will help you meet several other requirements, if they apply to your circumstances.

For example, you must include:

- a general description of your technical and organisational security measures in your record of processing activities, where possible; and

- details about the measures you intend to take to mitigate any risks you identify in your DPIAs.

You could also include these considerations:

- in your security risk assessments; and

- in any LIA you undertake.

Finally, you must also monitor the state of the art and ensure that the methods you use continue to be appropriate as techniques evolve.

Further reading – ICO guidance

- Accountability framework

- Guide to the UK GDPR – Security outcomes

- Guide to the UK GDPR – accountability and governance

- Our guidance on privacy-enhancing technologies (PETs) provides guidance on the use of state-of-the-art solutions that can be used for pseudonymisation, including Secure Multiparty Computation (SMPC) and homomorphic encryption.

What pseudonymisation techniques should we use?

The most common types of pseudonymisation techniques are:

- hashing;

- encryption; and

- tokenisation

Hashing-based pseudonymisation

Cryptographic hash functions transform input data of any size into fixed-length outputs. These outputs are known as ‘hash values’ or ‘message digests’.

Hashing is useful for checking the integrity of files. By comparing the hash of the current file with the hash generated when the file was first created, you can quickly determine if it has been modified. If the hashes match, the file remains unchanged; if they differ, it signals that the file has been potentially tampered with or corrupted.

Hashing is intended to be one-way. For example, if someone obtains a list of hash values, they should not be able to work out what the original input was, even if they know what hash function was used to create the values. Hashing can remove explicit links between people and the data. A mapping table is used to link between the input identifiers and the output hash. You should ensure you use a hash function that is appropriately robust in the circumstances. Using a robust hash function ensures an attacker cannot:

- calculate the original input;

- make educated guesses about the input (eg by knowing a list of hashed names); and

- find two inputs mapping to the same output.

If you are considering using a hashing function to apply appropriate technical and organisational measures to personal data, you should avoid using:

- hashing algorithms that do not use additional data to generate a pseudonym (eg a salt, pepper or encryption key); or

- outdated hashing algorithms (eg MD5 and SHA-1).

These algorithms are vulnerable to brute force identification attacks.

What hashing approach and algorithm should we consider?

The section below provides a summary of the strengths and weaknesses for some of the most common hashing techniques you could consider, as well as examples of suitable applications .

In order to mitigate identification attacks, random data (known as a salt or pepper) can be added to plaintext data before the hash function is applied. Unlike salts, peppers are not shared and are stored separately from hashes in a secure environment. For each different salt or pepper used, the resulting hashes also differ. If you require consistent hashes, then you are required to share the salt as well as the hash value, therefore there is a risk of brute-force attacks.

If you use salted hashes for linking the same person’s records between databases, you should ensure that appropriate technical and organisational measures are in place to protect the salt.

You could use a hashing algorithm such as bcrypt. This provides robust pseudonymisation by intentionally slowing down hash computation to deter brute-force attacks. It does this by significantly prolonging the time required to guess the plaintext (known as the work factor). As technology evolves, the work factor in bcrypt can be increased to maintain the same level of security. Bcrypt also automatically includes a unique salt during hashing to prevent identical inputs from producing the same hash.

Encryption-based pseudonymisation

Pseudonymisation can be performed with symmetric and asymmetric encryption. In symmetric encryption the same key is used for encryption and decryption.

In asymmetric encryption, one key is used for encryption and a different key is used for decryption. One of the keys is typically known as the private key and the other is known as the public key.

The private key is kept secret by the owner and the public key is either shared amongst authorised recipients or made available to the public at large.

This typically means that any party can encrypt data but only the owner of the private key can decrypt the data. Robust encryption relies on the security of the encryption key. You should choose an appropriate encryption algorithm, secret key length and security controls.

You could use symmetric encryption to generate consistent (also known as deterministic) or randomised pseudonyms for identifiers across different databases, depending on the encryption implementation.

You could use asymmetric or symmetric encryption to generate random pseudonyms for each use of the same identifier by using a probabilistic asymmetric scheme which adds randomisation into the process.

Depending on the circumstances, you could use other forms of encryption. For example, using format-preserving encryption to encrypt identifiers (eg an email address) as pseudonyms, while preserving the format of the data.

Other resources

“Data pseudonymisation: advanced techniques and use cases” (2021) by The European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) provides more details about other advanced encryption-based pseudonymisation techniques. (external link)

Tokenisation-based pseudonymisation

Tokenisation replaces identifiers with randomly generated tokens. Tokens can be generated by hashing or by generating random numbers that are stored in an indexed sequence.

Tokenisation is an efficient technique, and therefore it can be suitable for large-scale processing. As there is no mathematical relationship between a token and an original identifier, knowledge of a token does not allow an attacker to re-identify a person.

You could use tokenisation to link people across databases, providing you use the same token for the same person in each database.

Example

A bank uses tokenisation to link customer data across its various services, such as current accounts, savings accounts, and mortgage services. When a customer opens a current account, the bank generates a unique, random token to replace a customer’s direct and indirect identifiers in the bank's database.

The mapping between the customer's identifiers and the random token is stored in a separate, database managed by the bank's IT department with appropriate technical and organisational measures to prevent unauthorised access.

When a customer later opens a savings account or applies for a mortgage, the bank uses same token to link their financial records across these services. This allows them to link customer data across databases without exposing direct or indirect identifiers.

Further reading – ICO guidance

See our guidance on passwords in online services in the Guide to the UK GDPR for more information on appropriate hash functions in that context.

See our guidance on encryption in the Guide to the UK GDPR for more information on appropriate encryption algorithms and the required technical and organisational measures to implement them.

How should we assess the risk of attackers reversing pseudonymisation?

When choosing and implementing a pseudonymisation technique, you must consider the risk of the method being reversed to identify the people the pseudonymised data relates to. The likely types of attacks include:

- brute force attacks (also known as exhaustive searches);

- dictionary searches, which involve an attacker computing a set of possible pseudonyms at scale, saving the result, and using that information when attempting to reverse the pseudonymisation; and

- ‘guesswork’, based on the fact that some characteristics are more frequent than others.

The effectiveness of these attacks will depend on factors such as:

- the pseudonymisation technique you use;

- how you configure and implement that technique;

- the background knowledge of the attacker;

- the category of personal data the pseudonymous data relates to;

- the protections you put in place for the additional information; and

- the availability of other relevant information the attacker has access to.

Some attackers will focus on discovering the additional information, such as the pseudonymisation key or mapping table. If successful, this type of attack has the greatest impact as the attacker can re-identify all the pseudonymised data, completely reversing the pseudonymisation process.

You should assess the risk of an brute force, dictionary and guesswork attacks on the pseudonymised data by considering the following factors:

- Size of the identifier domain and the dataset (smaller is more vulnerable).

- Type of pseudonymisation function used and the likelihood of an attacker being able to compute the pseudonymisation function.

- The amount of additional information available, for example, the number of pseudonymisation secrets (eg keys, salts).

- Whether the pseudonym contains some information derived from the original identifier

You could implement the following measures to mitigate any risks of these attacks:

- Use appropriate key sizes, or long salts or peppers, if using hashing.

- Consider fully randomised pseudonymisation techniques.

- Use a technique that has no mathematical relation to the initial identifiers (eg tokenisation).

- Test whether it is computationally feasible to guess the pseudonymisation secret.

You should also consider the factors that may result in identification of a single person in pseudonymised data, for example:

- Ability to use ‘additional information’ without access to the pseudonymisation key.

- Combining common indirect identifiers used to match a person.

- The presence of outlier values.

You could implement the following measures to mitigate the risk of a person being identified:

- Consider if you can remove any attributes in the data that may reveal a single person without access to the pseudonymisation key (eg outlier values or rare characteristics).

- Apply appropriate technical and organisational measures to protect the additional information, such as encryption and access controls.

What organisational measures should we consider for pseudonymisation?

The UK GDPR requires that when you implement pseudonymisation, you must keep any additional information separated from the pseudonymised data using appropriate technical and organisational measures.

You must choose a technical solution for pseudonymisation that compliments the organisational measures you use. You must ensure that the technical measures are carried out effectively and appropriately. The additional information that can be used to identify people from a pseudonymised dataset is a source of risk, so you must put in place measures to protect it.

For example, you must:

- securely destroy the additional information if you don’t need it;

- store it securely (eg by encrypting it and using robust key management methods); and

- delete it from any insecure media, such as memory storage and systems.

What measures should you use to keep the additional information separate?

In order to ensure you keep the additional information separately, you should:

- store the additional information and pseudonymised data in distinct physical locations (eg using separate databases or network segmentation to prevent linkage);

- enforce strict access control policies to restrict physical and logical access to the additional information to only authorised personnel;

- encrypt the additional information so that even if unauthorised access occurs, the data remains unintelligible without access to the decryption key;

- implement a robust logging system to track access requests to the additional information, with regular reviews of these logs;

- handle and store the keys appropriately. This includes secure storage and rotation practices; and

- securely back up the additional information, so you can recover it if you need to. You should regularly test your backup and recovery process.

Other resources

A number of publications from the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA) provide more details about pseudonymisation techniques, including additional risks that you may need to consider.

These include:

- “Recommendations on shaping technology according to GDPR provisions" – an overview on data pseudonymisation” (2019) (external link)

- “Pseudonymisation techniques and best practices” (2019) (external link)

- “Data pseudonymisation: advanced techniques and use cases” (2021) (external link)